Inside the V8 Engine: A Deep Dive into JavaScript Execution

A technical walkthrough of the V8 JavaScript engine, covering the AST, Ignition interpreter, TurboFan JIT compiler, and optimization strategies like hidden classes.

The Black Box of Execution

As developers, we often treat the JavaScript engine as a black box. We feed it source code, and it performs actions. For most scripting tasks, this abstraction is fine. But when you are building high-performance Node.js backends or complex frontend applications, "fine" isn't good enough.

V8 is the open-source JavaScript and WebAssembly engine developed by the Chromium project. It powers Chrome, Node.js, and Deno. It is not a simple interpreter; it is a sophisticated piece of engineering that utilizes Just-In-Time (JIT) compilation to transform high-level JavaScript into highly optimized machine code at runtime.

In this analysis, we are going to tear down the execution pipeline: from the moment V8 receives a script to the moment CPU instructions are executed.

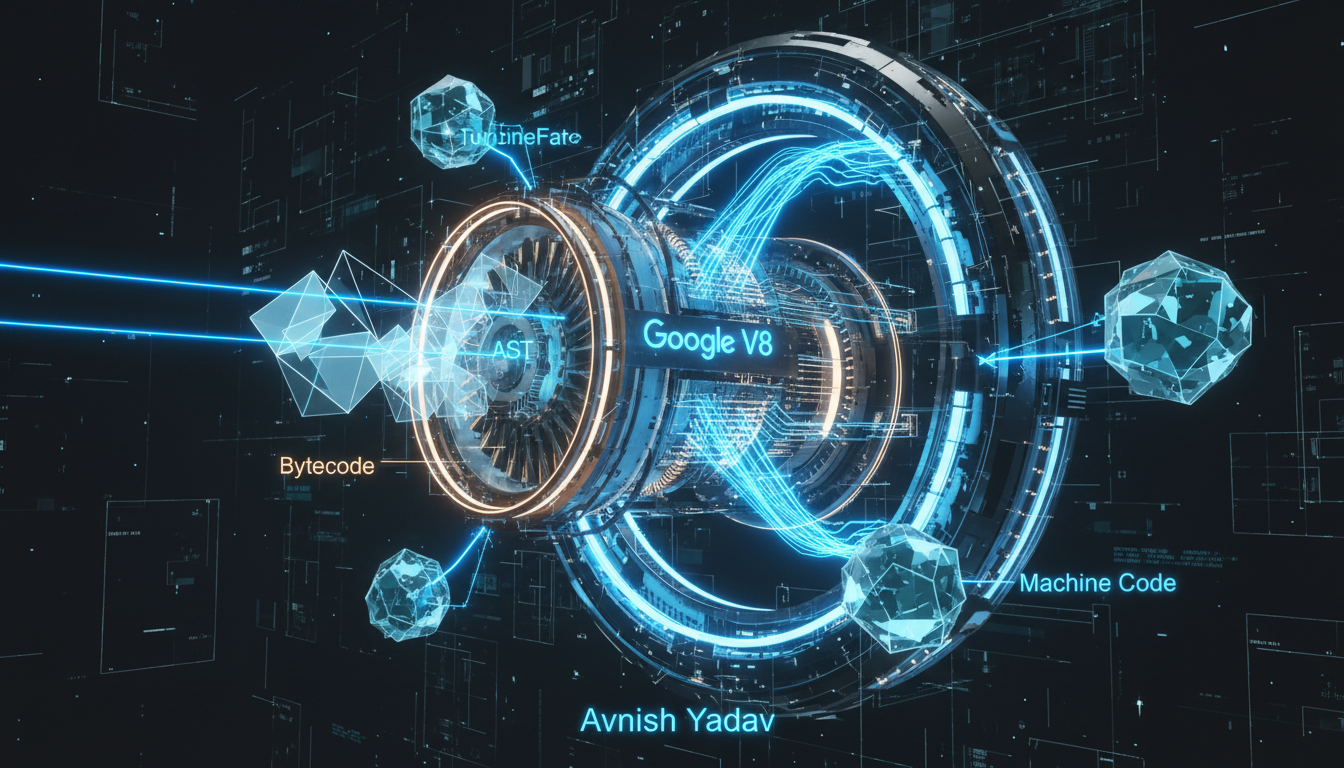

The V8 Architecture: A High-Level Pipeline

Before diving into specific components, let’s look at the flow of data. When V8 receives JavaScript code, it doesn't immediately compile it to machine code (which would slow down startup time), nor does it strictly interpret it line-by-line (which would be too slow for execution).

The pipeline consists of three distinct phases:

- Parsing: Breaking code into an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST).

- Interpretation (Ignition): Converting AST to Bytecode and executing it.

- Compilation (TurboFan): optimizing "hot" bytecode into Machine Code.

1. Parsing and the AST

The first step is lexical analysis. The Scanner breaks your code string into tokens. For example, const a = 10; becomes a series of tokens: keyword(const), identifier(a), operator(=), literal(10).

These tokens are fed into the Parser, which generates an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST). The AST is a tree representation of the syntactic structure of the code.

Engineering Note: V8 uses two types of parsing to optimize startup time:

- Eager Parsing: Parses functions that are executed immediately. It builds the full AST and catches errors.

- Lazy Parsing: For functions defined but not immediately called, V8 only does a light pre-parse to verify syntax. The full AST generation is deferred until the function is invoked. This is crucial for reducing the Time to Interactive (TTI) on web pages.

2. Ignition: The Interpreter

Once the AST is generated, it is passed to Ignition. Ignition is V8's interpreter.

Ignition's job is to strip the AST down to Bytecode. Bytecode is an abstraction of machine code. It is platform-independent and significantly smaller in memory size than machine code. This is vital for low-memory devices (like mobile phones running Chrome).

Ignition executes this bytecode. At this stage, your JavaScript is running. It isn't blazing fast yet, but it started up quickly. If a piece of code runs only once, it likely stays in the Ignition phase.

3. The Feedback Vector

While Ignition interprets the bytecode, it acts as a profiler. It gathers metadata about how your code behaves. This data is stored in a structure called a Feedback Vector.

V8 is looking for Hot Code. Hot code is code that runs frequently (loops) or is invoked often. V8 tracks:

- How many times a function is called.

- The shapes (types) of arguments passed to it.

- The results of operations.

When a function becomes "hot," V8 activates the next stage of the pipeline.

TurboFan: The Optimizing Compiler

This is where the magic happens. TurboFan is V8's optimizing compiler. It runs on a separate background thread so it doesn't block the main execution thread.

TurboFan takes the Bytecode from Ignition and the Feedback Vector containing the profiling data. It uses this data to make speculative optimizations.

Why "speculative"? JavaScript is dynamically typed. The engine can never be 100% sure that function add(a, b) will always receive integers. However, if the Feedback Vector says, "The last 1,000 times this ran, a and b were integers," TurboFan creates machine code optimized specifically for integers.

This optimized machine code eliminates the overhead of type checking and dynamic lookups, making it comparable to C++ or Rust speeds in specific scenarios.

Under the Hood: Hidden Classes (Shapes) and Inline Caching

To understand how to write optimized code, you must understand how V8 handles objects. In a static language like C++, an object's memory layout is fixed. In JS, you can add or remove properties on the fly. This makes property access slow because the engine typically has to do a dynamic lookup.

V8 solves this with Hidden Classes (internally called Maps or Shapes).

The Shape Transition Chain

Consider this code:

function Point(x, y) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}

const p1 = new Point(1, 2);Here is what happens inside V8:

- Map0: An empty object

{}is created. - Map1: When

this.x = xexecutes, V8 creates a new shape (Map1) based on Map0 that includes propertyxat offset 0. - Map2: When

this.y = yexecutes, V8 creates Map2 based on Map1 that adds propertyyat offset 1.

If you create another object const p2 = new Point(3, 4), V8 recognizes the structure and reuses the same transition chain and final Map2. This allows V8 to access properties via memory offset (like C++) rather than hash table lookups.

Inline Caching (IC)

TurboFan uses these Shapes for Inline Caching. When V8 sees code accessing p1.x, it caches the lookup result. It effectively rewrites the logic to: "If the object has the Shape of Map2, the value of x is at memory offset 0."

Deoptimization: The Bailout

This optimization system relies on assumptions. What happens if those assumptions are violated?

function add(a, b) {

return a + b;

}

// Hot code: V8 optimizes 'add' for integers

for(let i = 0; i < 10000; i++) {

add(i, i);

}

// Curveball: Passing a string

add("Hello", "World");Up until the loop finishes, TurboFan has compiled add into machine code that assumes integer inputs. When add("Hello", "World") is called, the machine code performs a check, realizes the input is not an integer, and fails.

This triggers Deoptimization.

- TurboFan throws away the optimized machine code.

- Execution returns (bails out) to Ignition (the interpreter).

- The bytecode is executed (which handles the string concatenation correctly but slowly).

- The Feedback Vector is updated to reflect that the function is now polymorphic (handling multiple types).

Deoptimization is expensive. It incurs the cost of switching execution contexts and rebuilding code.

Writing V8-Friendly Code

Understanding these internals leads to specific coding patterns that help V8 keep your code optimized.

1. Initialize Properties in Constructor

Always initialize object properties in the same order. This ensures objects share the same Hidden Class (Shape). If you add properties in different orders, you generate different Shapes, breaking Inline Caching.

// BAD: Creates two different shapes

const a = { x: 1 };

a.y = 2;

const b = { y: 2 };

b.x = 1;

// GOOD: Same shape

class Point {

constructor(x, y) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}

}2. Keep Functions Monomorphic

A function is monomorphic if it always receives arguments of the same Hidden Class (Shape) and type. If you pass different shapes to the same function, it becomes polymorphic (2-4 shapes) or megamorphic (5+ shapes).

Monomorphic functions run fastest because the Inline Cache only needs to check against one Shape. Megamorphic functions are significantly slower as V8 abandons local caching for a global lookup.

3. Avoid Large Numbers (Smi vs HeapNumber)

V8 stores small integers (Smi) directly in the pointer itself (using a bit-shift tag). Large numbers or doubles are boxed as objects (HeapNumbers). Mixing these heavily can cause subtle deoptimizations, though modern V8 is quite good at handling this. Stick to 31-bit signed integers where maximum performance is critical.

Summary

The V8 engine is a race car that builds itself while driving. It starts with the AST, interprets via Ignition to get moving, and uses the TurboFan compiler to upgrade parts of itself into a Formula 1 engine based on how you drive it.

By understanding the Parsing -> Ignition -> TurboFan pipeline, and respecting the rules of Hidden Classes and Feedback Vectors, you stop fighting the engine and start leveraging it.

Comments

Loading comments...