Mastering the Metal: Essential Web APIs & Browser Internals for Frontend Engineers

A technical guide to the browser environment. Learn to leverage Native Web APIs, understand the Critical Rendering Path, and implement robust Client-Side Storage strategies without relying on heavy libraries.

The Era of Abstraction

We live in a golden age of frontend development. React, Vue, Svelte, and Next.js have abstracted away the messy reality of the DOM. But there is a ceiling to how good you can be if you only understand the abstraction layer.

As an automation engineer, I often find myself debugging issues where the framework isn't the problem—the platform is. When you are building complex dashboards, intelligent agents that live in the browser, or high-performance micro-SaaS tools, you need to understand the environment your code lives in.

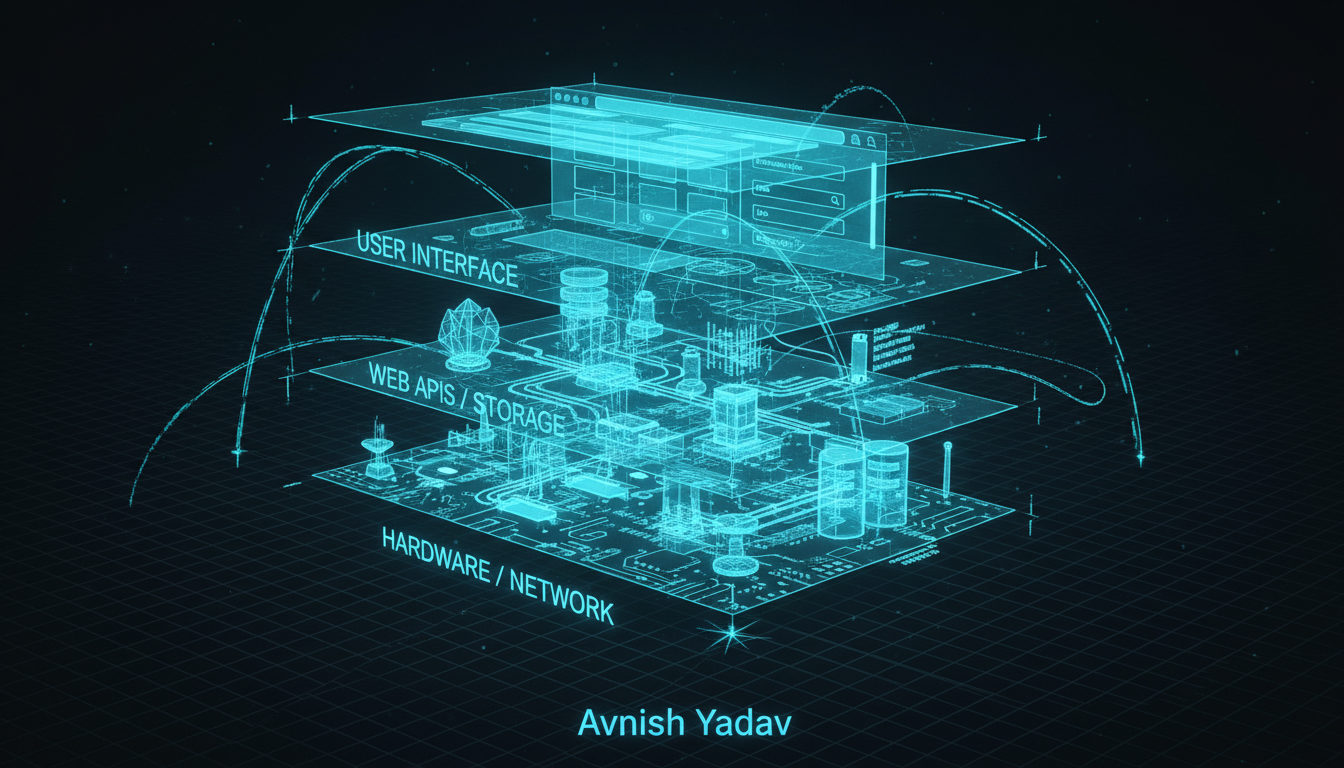

The browser is essentially an operating system. To build efficient software, you need to understand its file system (Storage), its kernel (The Engine/Event Loop), and its I/O (Fetch/Network). This post covers the essential Web APIs and concepts that I rely on when building systems, moving beyond the syntax of JavaScript and into the architecture of the web.

1. The Object Model: DOM vs. BOM

Before diving into APIs, we need to distinguish between the two primary interfaces we interact with.

The Document Object Model (DOM)

Most developers know this. It is the tree structure representation of your HTML. Frameworks utilize a Virtual DOM to batch updates because touching the actual DOM is expensive.

Performance Tip: The most expensive operations in the browser are Reflow (calculating layout) and Repaint (applying pixels). Accessing geometric properties (like offsetHeight) forces a synchronous reflow. When building animations or drag-and-drop interfaces, avoid reading layout properties in a loop.

The Browser Object Model (BOM)

This is everything outside the page content. It includes the window, navigator, location, and history objects. This is where the hardware lives.

- Navigator: Gives access to user agent, clipboard, and hardware concurrency (vital for Web Workers).

- Location: Not just for reading the URL, but for manipulating the browser history stack without triggering full page reloads (the basis of SPAs).

2. Network Requests: Beyond Axios

While libraries like Axios are great, the native Fetch API has evolved to the point where external dependencies are often unnecessary for modern micro-SaaS applications.

However, simply using await fetch() isn't enough. You need to handle the edge cases regarding request cancellation and streams.

The AbortController

When building AI agents or search interfaces, users often change their input before the previous request finishes. If you don't cancel the old request, you create race conditions and waste bandwidth.

const controller = new AbortController();

const signal = controller.signal;

// Start a request

fetch('/api/heavy-data', { signal })

.then(response => response.json())

.then(data => console.log(data))

.catch(err => {

if (err.name === 'AbortError') {

console.log('Fetch aborted');

} else {

console.error('Fetch error:', err);

}

});

// Cancel it if the user navigates away or types again

controller.abort();3. Client-Side Storage Architecture

This is where we will focus our practical experimentation. Modern applications need to persist state. While Redux or Zustand handles state in memory, that state is lost on refresh. You have four primary options for persistence, each with specific use cases.

Cookies

Capacity: ~4KB

Use Case: Authentication tokens only.

Cookies are sent with every HTTP request. Storing data here bloats your network traffic. Do not use cookies for application state.

Local Storage

Capacity: ~5MB

Persistence: Until explicitly deleted.

Use Case: UI preferences (Dark mode), semi-permanent user settings.

Local Storage is synchronous, meaning large read/write operations can block the main thread. It works strictly with strings, so you must serialize JSON.

Session Storage

Capacity: ~5MB

Persistence: Until the tab is closed.

Use Case: Form data in multi-step wizards, temporary session state.

This is the most underused API. It is perfect for single-page applications where you want to preserve the user's place if they accidentally refresh, but you don't want that data persisting next week.

IndexedDB

Capacity: GBs (Disk space dependent)

Use Case: Offline applications, caching large datasets, complex querying.

IndexedDB is asynchronous and transactional. It's an object database inside the browser. If you are building a "Local-First" app (like a notion clone), this is your backend.

4. Practical Build: The "Resilient Form" Wrapper

Let's write a utility that utilizes both Local Storage and Session Storage to solve a common problem: Users losing data when they accidentally close a tab or refresh.

We will create a helper class that saves draft data to sessionStorage on every keystroke (high frequency, temporary) and allows saving to localStorage for drafts meant to be kept longer.

class StorageManager {

constructor(prefix = 'app_v1_') {

this.prefix = prefix;

}

// Helper to handle JSON serialization

_set(storageType, key, value) {

try {

const serialized = JSON.stringify(value);

window[storageType].setItem(this.prefix + key, serialized);

return true;

} catch (e) {

console.error('Storage quota exceeded', e);

return false;

}

}

_get(storageType, key) {

const item = window[storageType].getItem(this.prefix + key);

if (!item) return null;

try {

return JSON.parse(item);

} catch (e) {

return item;

}

}

// Session: For accidental refreshes

saveSession(key, value) {

return this._set('sessionStorage', key, value);

}

getSession(key) {

return this._get('sessionStorage', key);

}

// Local: For long-term preferences

savePermanent(key, value) {

return this._set('localStorage', key, value);

}

getPermanent(key) {

return this._get('localStorage', key);

}

}

// Usage Example

const storage = new StorageManager('draft_tool_');

// Imagine an input field listener

const inputField = document.querySelector('#blog-content');

// On load: Check if we have a session draft

const savedDraft = storage.getSession('current_post');

if (savedDraft) {

inputField.value = savedDraft;

console.log('Restored from session!');

}

// On Input: Save to session

inputField.addEventListener('input', (e) => {

storage.saveSession('current_post', e.target.value);

});

This simple pattern dramatically improves UX. It decouples the UI state from the database state, ensuring the user never loses work due to browser volatility.

5. The Event Loop & Asynchronous JavaScript

Understanding the Event Loop is what allows you to debug "freezing" UIs. JavaScript is single-threaded. It has one Call Stack.

When you run fetch or setTimeout, you aren't blocking the stack. You are handing work off to the browser (Web APIs), which pushes a callback into a Queue when done.

Microtasks vs. Macrotasks

Not all queues are equal.

- Macrotasks (Task Queue):

setTimeout,setInterval, I/O. - Microtasks (Job Queue): Promises (

.then/catch/finally),queueMicrotask, MutationObserver.

The Golden Rule: The Event Loop processes all microtasks before moving to the next macrotask. This means if you have a Promise chain that loops recursively, you can block the entire browser rendering process (event loop starvation), whereas a recursive setTimeout will allow rendering in between calls.

6. Intersection Observer API

Old school "scroll listeners" are performance killers. Attaching a listener to the scroll event fires the function hundreds of times per second.

The Intersection Observer API offloads this to the browser engine. It tells you, asynchronously, when an element enters or leaves the viewport.

I use this extensively for:

- Lazy Loading Images: Only fetch the image when the user scrolls near it.

- Infinite Scrolling: Trigger a database fetch when the user hits a "footer" element.

- Analytics: Tracking if a user actually read a section of a blog post.

const observer = new IntersectionObserver((entries) => {

entries.forEach(entry => {

if (entry.isIntersecting) {

console.log('Element is visible!');

// Load data or animate

entry.target.classList.add('fade-in');

// Stop observing once done

observer.unobserve(entry.target);

}

});

});

observer.observe(document.querySelector('.lazy-load-target'));Conclusion: Build for the Platform

Frameworks come and go. I spent years writing jQuery, then Angular, now React. The common denominator through all of them was the Browser Object Model.

By mastering Storage APIs, the Event Loop, and efficient Network patterns, you write code that is framework-agnostic and significantly more performant. You stop fighting the browser and start leveraging it as the powerful operating system it is.

Next Steps: Take the StorageManager code above and extend it. Try adding an expiration time to the LocalStorage items so your app cleans up after itself. That is how you turn a script into a system.

Comments

Loading comments...